Well, I seem to be one of those “occasional” bloggers, but it’s not for lack of desire to blog. It’s more like a lack of time and energy to blog. Sometimes I post to work things out, other times I blog to visualize what I think I’ve already worked out. This time, it’s to give an update on the progress of the dissertation, as well as talk a little bit about my new Twitter project, translating the Ormulum in tweets, during which I have discovered something absolutely crucial to Orm’s work.

First, however, the dissertation. I met with my advisor this past week to discuss my most recent 63-page chapter on Poema Morale and its manuscripts, which is why I took off a few weeks from tweeting Orm, and because this chapter felt a little different from my Ormulum chapter, I could tell that our meeting was going to involve a new direction or format for my dissertation. I was not disappointed. In fact, my third text, Ancrene Wisse, got the ax, with which I was okay since I knew the least about that work and had never seen its 9 English, 4 French, and 4 Latin manuscripts. In sum, cutting out AW has made me much less stressed out about the dissertation and my desire to finish, defend, and graduate in May 2015.

Now, my task will be to divide both of my present chapters into two more chapters, thus turning my dissertation into an Ormulum and Poema Morale project with a hefty introduction, four body chapters, a brief conclusion, and an appendix with all seven of of my Poema Morale diplomatic transcriptions. That’s right. All seven will be accessible in one place. You’re welcome, Internet. The vision we have for the chapters is that both texts will get one chapter dedicated to their manuscript contexts, which means the one for PM may very well be longer than that of the Ormulum‘s because it has six manuscripts to Orm’s one. The second chapter will be dedicated to a specific reading within the texts; for the Ormulum, that will be my reading of the “sea-star” epithet in Homily 3 (from Luke), and for PM, that will be a specific reading of the Lambeth text, which ends forebodingly with the words “fordon and fordemet” (“destroyed and condemned”). No happy ending for the Lambeth readers, I’m afraid, which is why, of course, I’m in love with that version. So, that’s the current state of the dissertation. My goal for the rest of this semester is to divide the PM into two whole chapters (roughly 35-45 pages each) to give to my committee by May 5. Done. I can totally do that. Then, during the summer, I’ll begin dividing the Ormulum chapter and making notes towards my Introduction, which I’ll write, along with the brief conclusion, in the fall. Thus, by September 1, I’ll have two to three chapters fully fleshed out with an outline of my Introduction ready. Job market, here I come. RAR!!!

Now, on to the Twitter project and my revelation, which may be obvious to those who know the Ormulum as intimately as I do. But still.

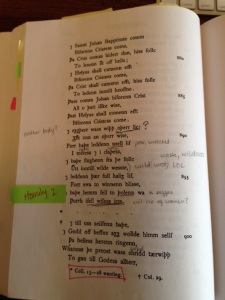

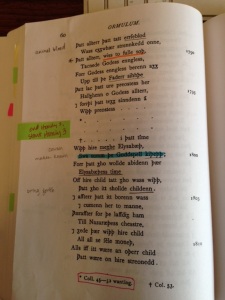

For those of you who don’t know the Ormulum and its manuscript as well as the handful of us who are obsessed with it, there are a few things you should know, the most important of which is that the manuscript has several folios missing. Unfortunately, the 1878 Robert Holt edition with notes and glossary by Robert Meadows White, which is the only edition of Ormulum we currently have, lays out the text in such a way that, if you’re not paying attention to the occasional asterisks (*), you could never tell that the manuscript is missing “columns”–that’s the other thing, he doesn’t note folios, like most scholars do, he notes the columns of writing, and there are normally two columns per page (four columns per folio/leaf). Here’s an example of what I mean:

Aside from my highlighting, underlining, circling, and marginal notes, do me a favor and look at those dots, the asterisk, and the columns noted as “wanting” at the bottom. Sure, they imply that something is missing, but what would you think that means based on all the other lacunae you’ve experienced as a scholar? Or, as a lay reader who doesn’t know much about missing folios or words rendered illegible or missing in manuscripts, what would those dots say to you? Well, the first thing that it tells me is this, “Yep, text is missing, and I’ve acknowledged that, but, guess what, it’s still the same homily!” Just kidding. It’s not. In fact, what you’re missing is the end of Homily 2 and the beginning of Homily 3, but you wouldn’t know that because, the first bits of missing folios don’t tell you that you’ve transitioned from Homily 1 to Homily 2 either:

Aside from my highlighting, underlining, circling, and marginal notes, do me a favor and look at those dots, the asterisk, and the columns noted as “wanting” at the bottom. Sure, they imply that something is missing, but what would you think that means based on all the other lacunae you’ve experienced as a scholar? Or, as a lay reader who doesn’t know much about missing folios or words rendered illegible or missing in manuscripts, what would those dots say to you? Well, the first thing that it tells me is this, “Yep, text is missing, and I’ve acknowledged that, but, guess what, it’s still the same homily!” Just kidding. It’s not. In fact, what you’re missing is the end of Homily 2 and the beginning of Homily 3, but you wouldn’t know that because, the first bits of missing folios don’t tell you that you’ve transitioned from Homily 1 to Homily 2 either:

One little line of dots to tell you that 16 columns, or, if we do the math, 4 folios are missing. However, Holt continues the text in his short lines like nothing has happened. Even the line numbers pick up where they left off! “Don’t mind the dots. It doesn’t really mean anything…” What if the text were laid out in long lines, though (as I’ve been writing in my posts)? And what if the text were properly separated into specific Homilies instead of what looks like one large poem with occasional breaks/sections? Would it be more welcoming to read? I bet it would be. Instead of saying, “I’m going to read X amount of lines,” we could say, “I’m going to read Homily 14 (which is complete, by the way).” Returning to the dots again for a moment, I’d like us to consider something else: one line of dots signals 16 missing columns (4 folios) while four lines of dots signal 8 missing columns (2 folios). Isn’t that a little disproportional?

Anywho, that’s a lot of whining to emphasize our need for a new edition, and, luckily, the Early Middle English Society is working on the Archive of Early Middle English to address this problem. The biggest problem that I’ve run into with the missing folios, other than trying to figure out in which Homily the “sea-star” passage occurs (it’s the third one), is my Twitter project of translating Orm’s work. I reached line 898 and thought, ‘Well, what do I do now?’ I knew that there was a manuscript (London, Lambeth Palace Library, MS 783) that contained transcriptions and notes by Francis Junius (1589-1677) and Jan van Vliet (d. 1666), and Vliet had supposedly transcribed some of the text from the now-missing folios of the Ormulum. I had not seen the manuscript myself, though I’ll see it this July when I revisit the Lambeth Homilies (MS 487), but, luckily, N. R. Ker had published these transcriptions!

So, obviously, I quickly found his article: “Unpublished Parts of the Ormulum Printed From MS. Lambeth 783,” Medium Ævum 9.1 (1940): 1-22. Ker helpfully listed the portions of the missing columns of the Ormulum that Vliet had transcribed, and I’ll list them below for your convenience (if you don’t care about them, skip on ahead):

(1) about 360 lines from columns 13-28, of which the first 10 belong to the end of Homily i and the rest to Homily ii,

(2) about 42 lines from columns 45-48 (Homily ii),

(3) about 62 lines from columns 69-76, of which the first 2 are from the end of Homily iv and the rest from Paraphrase v, Homily v, and Paraphrase vi,

(4) about 51 lines from columns 97-101, 103 (Homily viii),

(5) 4 lines from column 160 (Paraphrase x). [Ker 2]

You may notice, however, that Ker approximates these line numbers because, as Ker writes, “If Vliet’s excerpts of extant passages are compared with the MS., it is seen that nearly all the numerous deviations from the exemplar are due to the disregard of the peculiarities of Orm’s spelling and of minor details” (2). Alright, the “peculiarities” of Orm’s standardized orthography are changed to something more “standard” to Middle English as Vliet understood it, right? Okay, I can deal with that. Then Ker writes, ” The real errors of transcription are few” because Vliet’s real “interest was lexicographical and his excerpts […] are not continuous blocks of text, but illustrations of the use and meaning of particular words and phrases” (2-3). WHAT?! How is that not an illustration of “real errors” in his transcription? He lifts words from “the middle of a line,” “include[s] an essential word from further up the column,” or “omit[s] words or lines which were not strictly necessary to the sense” (3, emphasis added). Finally, Ker tells us the true use of Vliet’s transcription, which has “evidently no value for reconstituting an exact text”: “They are important because, together with the word-list on ff. 43v-51, they contain a considerable number of new or rare words, copied in an essentially correct form” (3, emphasis added).

Well, let me tell you, after reading and translating these excerpts, even the ones that are more fully transcribed, it is difficult to gain the full sense of many of these lines. Ultimately, what this told me was that the “peculiarity of Orm’s spelling” and, most especially, his repetition–those “words or lines which were not strictly necessary to the sense”–are, in reality, CRUCIAL to understanding Orm’s work to our fullest extent possible. It is harder to translate Vliet’s extracts for me than it is to translate Orm’s writing. At the beginning of my Twitter project, I had a moment to consider whether or not I should condense Orm’s repetition for the sake of the medium. After all, how many people want to read the same basic thing tweeted four times? However, upon further consideration, I decided that it would be a disservice to Orm’s work to limit his translation in such a way, even if it were mediated through Twitter. Luckily, it seems that I was right not to condense, to pick and choose, to censure Orm because, in doing so, we would have lost the nuance and the depth of meaning he was trying to communicate. This leads me to a better understanding to my first reaction to Christopher Cannon’s chapter on the Ormulum in his Grounds of English Literature, which is an incredibly important work that anyone even remotely interested in Early Middle English should read. Cannon’s book, which also includes thought-provoking discussions on The Owl and the Nightingale, Laȝamon’s Brut, and Ancrene Wisse, was an influential contributor to the new attention only a handful of scholars were paying to the literature of the Early Middle English period in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

He praises the form of Orm’s work over its content, even saying that the text’s “claim to fame may be that it proves better than almost any other text that a form can be smarter than its maker” (86). Cannon’s discussion of spellen (“to preach” but also “to spell”) links Orm’s notion of knowledge to the “verbal,” which he describes through Orm’s own engagement with John 1:14 (And the Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us): “[…] since Christ in such an account is not only God made flesh but an utterance–not only God’s ‘Son’ but a speech act–precisely as he is the Word, he is the product of a divine act of spelling” (91, his emphasis).

For Canon, then, Orm’s “‘spelling’ leads to more spelling and, therefore, never ends” (94), which leads to the “continuous statement” of the Ormulum, “in the constant movement from equivalence to equivalence which prevents any single term from gaining priority over any other” (95). I’ll leave aside my comments on Cannon’s statement that the contents of the Ormulum “wholly failed to find an audience in its day” (97) to get to Cannon’s engagement with self-acknowledgment and repetition. He writes:

And yet as Orm’s asides in this quotation make clear (‘as I said a littler [sic] earlier . . . as I said before’) to precisely the extent that it is aware of itself, repetition is also the doubt that a set of words may not have worked as they ought to have done, the retracing of a signifying groove that necessarily casts doubt over whether that groove was adequately traced in the first place. As the Ormulum unfolds by means of such repetition, as it spins itself out in concentric loops of identical words and sentences, each of them closing ever more tightly upon itself, as on repetition leads directly to another, as, in short, the poem becomes repetition, the resulting pattern recognizes the impulse to repeat in any form (that there ever are repeated words in a text or between them) actually undermines signification. In fact, it suggests that, if repetition is ever of any use, then what repetition knows is that words may not work at all. (99, his emphasis)

Clearly, my first instinct was that I loved the Ormulum and wanted to shield it from the criticism that it has experienced for over a century. That was the novice Ormulum student in me. As my more mature self, though still not an expert on the Ormulum as a whole–I don’t know that I’ll ever call myself an “expert” in anything, no matter how much my advisor does so herself–I can admit, Cannon is right. The problem that I see now, however, is that this reading seems to be based on the assumption that the Ormulum, which in its original form was around likely over 100,000 lines long, should be approached as one meditative poem. And this assumption, in turn, seems to be encouraged by another assumption, namely, that Orm’s work was hardly read by anyone; instead, this assumes that Orm was participating in something more like a personal devotional exercise. Another way of reading the Ormulum, however, would be to take Orm at his word and to honor his intentions in writing his collection. By doing so, we would see that these texts are separate Homilies that should be read as such, or would have been read as such in their original context. There are even a few large capitals to mark the opening of Homilies, as Mark Faulkner explains in the description of Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS Junius 1 in The Production and Use of English Manuscripts 1060 to 1220: “Multiple-line unadorned monochrome initials open most homilies. These are mostly in black, but there are several in green.” This manuscript tradition follows the Old English tradition and uses red, black, and green (amongst some other colors) in capital letters to begin new texts. See, for example, the Homily on the Assumption of the Virgin Mary on folio 66v of Cambridge, Trinity College, MS. B. 14. 52 (late 12th century), which also contains the “sea-star” epithet for Mary.

Although I don’t have an image of one of the green capitals in the Ormulum, I do have an image of a couple of black capitals, one that is an outline and one that is filled in with black ink. These may give us a clearer picture of the sort of capitals, which would have been green or red most likely, would have looked like:

I should also mention at this point that separating texts with capitals was not an exclusively 12th-century phenomenon. We see it in Old English manuscripts all over the place, such as in the Vercelli Book. Therefore, the use of capitals, especially without the use of rubrics, is a very vernacular English tradition, and Orm participates in this tradition fully. Based on these capitals then, the likely conclusion is that Orm intended this work to be read as individual Homilies, not a long single text, and, perhaps more importantly, the targeted audience was the uneducated English laity. Orm’s repetition and concern with self-awareness and self-acknowledgment seems to fit more securely into the homiletic and oral traditions than anything else. While I can understand the idea of repetition representing the failure of words themselves, as Cannon explains here,

What the larger pattern of such unmarked repetition may therefore be said to recognize in the Ormulum is what any reader who tries to find traction in its seamless circling also knows: using words can actually exhaust their capacity to mean, since it is possible to use them to such an extent that they can actually cause us to know less. (102, his emphasis)

I believe that the opposite is true when we actually sit and read the Ormulum, particularly if we read it aloud to ourselves or endeavor to translate it. With the experience of reading Vliet’s extracts in comparison to Orm’s own words to gird me, I can say fairly confidently that Orm’s repetition actually makes his meaning more clear than they might otherwise be. Particularly because some of his words are “new and rare,” we need the repetition to make clear not just his “sense” but also the deeper meaning behind his words. His theology is seemingly orthodox–I say “seemingly” because he seems to really love him some Mary–though his form and style are beyond unorthodox, but that’s what makes him fun.

To follow my Ormulum tweets on Twitter, you can find me @cmthomas or the tweets through the hashtags #ormulum, #orumulumH1, or #ormulumH2.